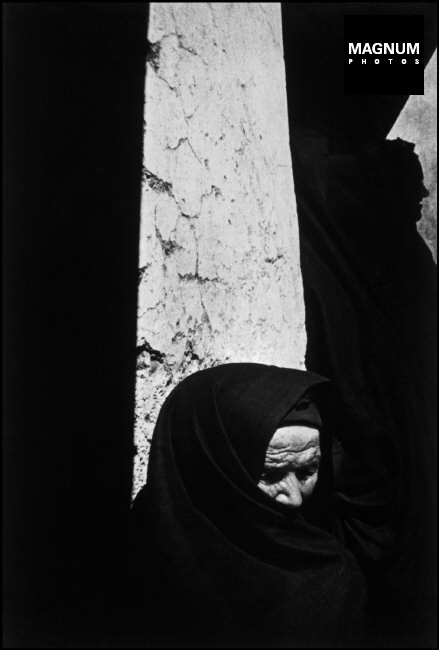

Fig 1 – A woman at the wake of Juan Carra Trujillo.

from the series “Spanish Village” – Eugene Smith 1951

Assignment 3 will be based on a small Italian village and as research towards this project I have looked at Eugene Smith’s Spanish village, which was published by Life Magazine in 1951 (1). I have previously reviewed two of Gene Smith’s photo essays Country Doctor (here and here) and Minamata (here).

W. Eugene Smith

As a Life and later a Magnum photographer Smith is the epitome of a “concerned photographer”, he immersed himself in his projects to such an extent that his editors often despaired of him ever concluding them. In a revealing letter to Bill Jay in 1969 he described how he had fought deadlines:

“I fought such as the hysteria of deadline being applied to the pyramids.” (2:p.112)

The letter includes other insights into the mind of this complex and troubled man but the comparison of his work to building the pyramids has a particular resonance. Following his departure from Life Magazine in 1955 Smith joined Magnum who found him an assignment to photograph Pittsburg for a book by Stefan Lorant. This was intended to be a three week job but Smith spent two years photographing the city, missing the deadline for Lorant’s book and turning down Magnum’s last ditch attempt to sell his series because the potential publisher would only use half the pictures Smith believed they needed to tell the story. (3) Smith was to break with Magnum and according to Chris Boot he left “broke” with Magnum “smarting from the investment it had made in Pittsburg”. (5:p.435)

His career had started on a local newspaper in 1936 photographing the environmental and social disaster of the “dust bowl” but his reputation was established during WWII as a war photographer in the Pacific theatre. He was severely injured at Okinawa taking two years to recover from his wounds.

In The Genius of Photography (4:p.115) Gerry Badger puts Smith’s post war work into the context of two opposing ideologies that prevailed in post war Europe, for many the reaction to the horror of a six year war was to withdraw into one’s self and soley take responsibility for one’s own actions; Badger labels this as the negative response. The positive response was the humanist approach of heightened social concern, a response that Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Capa, Gene Smith and their fellow Magnum photographers exemplified. They became known as “concerned photographers”.

Smith epitomised this approach, an obsessive artist who was notoriously difficult to work with, who progressed from sentimental narratives with political undertones about “good people” such as Country Doctor (1948) and Nurse Midwife (1951) to an in-depth study of Pittsburg (1955 to 1957) and finally to Minamata (1975). This was a move from sentimental observer to involved crusader but he was forever an outsider; although one might argue that being wounded in WWII and beaten up by company thugs during his Minamata project meant he had, what the American’s call “skin in the game”.

Writing in Magnum Stories Chris Boot refers to Smith as a man who “towers over the history of the magazine photo essay” (5:p.434) whom many believe was “the genius of twentieth-century photojournalism”.

Gene Smith died in 1978.

Spanish Village

The series as published in Life bears the hallmarks of Smith’s preferred style with deep blacks reminiscent of Bill Brandt or Josef Koudelka bringing a dark tone, in every sense of the word, to his portrait of a community apparently trapped in its medieval lifestyle. Unlike County Doctor Spanish Village is not constrained by a photo essay narrative approach, it is a more general observation of the village’s life. In 1951 the American audience for Life Magazine was experiencing a post war boom, I Love Lucy premiered on US television that year, colour television was broadcast for the first time, average family income was just less than $4,000 a year and the surge in private car ownership had led to the beginnings of a huge road building programme. Yet in April of that year they opened Life Magazine to see a Spanish village not just frozen in time but struggling to leave the middle-ages. There are no cars here, roads are dirt or primitive with broken cobbles, donkeys are the only form of transport, the fields are ploughed by man and beast, a farm labourer earns 30 cents plus one meal a day, no one smiles, and daily life is regimented by the church and Franco’s Guardia Civil. Life had a distinct tendency to use its stories to promote the American dream, look how good life is here and how bad it is everywhere else. I would suggest that this approach has been perpetuated by the American media ever since and has led to America’s apparent inability to understand or value cultures other than their own.

Boot discuses Smith’s approach to photo essays based on interviews he gave in the sixties. (5:p.434) Smith states that he started with his prejudices, recognised them as such and then started looking for new viewpoints.

“You cannot be objective until you try to be fair. You try to be honest and you try to be fair and maybe truth will come out.”

Each night he would record his thoughts on white cards and begin to map out the layout of the story. By doing this he could identify missing links and plan his next day’s shooting. Reading the explanation of his approach it is easy to understand how a two week project could grow into two years. If his subject was too large, the City of Pittsburgh for example, there would always be missing photographs, links to be made and gaps to fill. It explains why his relationship with editors and photo journalism as a profession was tempestuous. His explanations also show that he was planning layouts during the assignment, like Walker Evans, he wanted editorial control of his work but he was working within the rigid environment of a weekly magazine where photo stories were pre-scripted, deadlines sacrosanct and space tightly managed by the picture editor.

Life published seventeen photographs in their photo essay, Magnum clearly have access to more of Smith’s archive and include nearly sixty under the title of Village of Deleitosa in Western Spain. 1951 (6). This much larger collection better expresses Smith’s vision of the village and reflects his approach of honesty and fairness. The medieval elements are still present, but we can now see how the Life editors selected those images to the exclusion of providing any balance. In the more complete collection we see smartly dressed mothers with their children, one child has what appears to be a new bicycle; the market square has a modern feel, children walk to school carrying briefcases, the square is paved, a vending machine stands outside a shop; two children and an adult smile for the camera as they play football against the church wall complete with a stencilled portrait of Franco and there is evidence of a public garden. Having said that, there is no doubt that, in comparison with America in the fifties this was a backward community, living an agrarian peasant lifestyle that would have been familiar to their ancestors.

The selection and sequencing of the essay is probably not Smith’s work so I won’t consider that here but I do want to look at the overall type of photograph he captured. It is noticeable that in the Life series every picture is a human portrait of one form or another, in the larger Magnum collection that is one exception, a photograph of another Franco stencil and even that is, of course, a face.

Stylistically, whilst the Life series is dark, it is straight realism, journalistic in nature. Arguably the one exception is the woman carrying the tray of bread were she is represented as a silhouette, a pure form entering the doorway like a shadow puppet, even her stance, caught in the act of kicking open a door whilst maintain the balance of the tray appears puppet-like and unreal. In the Magnum series there are several more ambitious photographs where Smith has used the strong Mediterranean light to its full advantage creating powerful contrasts between jet black shadows and the sunlit streets; fig. 1 at the top of this essay is probably the best example, a quite stunning, Brandt-like photograph, that was clearly too strong for the tastes of the Life picture editors.

Fig 2 Villagers beating the corn kernels after the harvest. Once the straw is broken away, the wheat kernels are swept into a pile and tossed into the air. From the series “Spanish Village” – Eugene Smith 1951

Whilst, as mentioned above neither the Life nor the Magnum series form a strong narrative, many of the individual photographs offer little stories that make the series come alive. As can be seen in fig. 2 Smith is a great composer, the three women are carefully distributed across the frame and the story of threshing grain is told in a single photograph. There may be an underlying message about Franco’s rule, the Life editors obviously thought so by focusing so strongly on the picture of the Guardia Civil which was run with the caption:

“These stern men, enforcers of national law, are Franco’s rural police. They patrol countryside, are feared by people in villages, which also have local police.”

The Magnum series shows Smith’s desire to provide a complete picture of this village although I have been unable to find any information on the length of time he spent there or even why this village was chosen. He has created a record of Franco Spain before the tourist boom began to super-charge the economy. My tutor recently challenged me to express what I thought of my subjects and I have tried to analyse this series in that context. We know that Smith has a strong social conscience, twenty years later he was being beaten up for exposing the extent and human cost of industrial pollution in Japan and the pictures of Franco stencils and the smartly dressed Guardia Civil that contrasts with the clothes of the peasants might suggest a political undertone to the series. However, I sense that Smith was primarily interested in telling the story with great pictures rather than making a particular point. It is easy to assume, as a New York picture editor in 1951, or now living in a sort of equalised Europe that the peasant way of life described here was exceptional, a symptom of Franco’s mismanagement of Spain but I suggest that this is far from the truth and perhaps Smith understood this.

Britain in the fifties was not the exciting, culturally advanced, boom country of the sixties. Europe as a whole was still rebuilding after WWII, rationing was still in force in Britain and probably in many other counties. Spain had sat out the World War but was still recovering from a bloody civil war that was made considerably more violent by the intervention of Nazi Germany on one side and Soviet Russia on the other. Spain, Portugal, Italy and Greece all had large rural populations following a true peasant lifestyle, subsistence farming, the land still owned by the rich minority, the church a powerful political and social force whose best interests appeared to lie in maintaining the status quo.

My concussion is that Smith endeavoured to create a straight, truthful and balanced documentary of the village; his intent was to some degree perverted by his editors but his series stands the test of time and remains one of the few comprehensive studies of a pre-European Union rural lifestyle.

The photographs that follow are those published by Life in 1951.

Notes on Text

(i) The original text that accompanied the series is as follows:

The village of Deleitosa, a place of about 2,300 peasant people, sits on the high, dry, western Spanish tableland called Estramadura, about halfway between Madrid and the border of Portugal. Its name means “delightful,” which it no longer is, and its origins are obscure, though they may go back a thousand years to Spain’s Moorish period. In any event it is very old and LIFE photographer Eugene Smith, wandering off the main road into the village, found that its ways had advanced little since medieval times.

Many Deleitosans have never seen a railroad because the nearest one is 25 miles away. Mail comes in by burro. The nearest telephone is 12 miles away in another town. Deleitosa’s water system still consists of the sort of aqueducts and open wells from which villagers have drawn water for centuries . . . and the streets smell strongly of the villagers’ donkeys and pigs.

[A] small movie theater, which shows some American films, sits among the sprinkling of little shops near the main square. But the village scene is dominated now as always by the high, brown structure of the 16th century church, the center of society in Catholic Deleitosa. And the lives of the villagers are dominated as always by the bare and brutal problems of subsistence. For Deleitosa, barren of history, unfavored by nature, reduced by wars, lives in poverty—a poverty shared by nearly all and relieved only by the seasonal work of the soil, and the faith that sustains most Deleitosans from the hour of First Communion until the simple funeral that marks one’s end. (1)

Sources

Books

(2) Jay, Bill (1992) Occam’s Razor. Tucson: Nazraeli Press

(4) Badger, Gerry (2007) The Genius of Photography: how Photography has Changed our Lives. London: Quadrille.

(5) Boot, Chris (2004) Magnum Stories. London: Phaidon Press

Internet

(1) Cosgrove, Ben (2013) Spanish Village: W. Eugene Smith’s Landmark Photo Essay (accessed at Time Life 20.4.16) – http://time.com/3876243/life-behind-the-picture-w-eugene-smiths-guardia-civil-1950/

(3) Middlehurst, Steve (2014) W. Eugene Smith – WW2 to Minamata (accessed at Steve Middlehurst WordPress TAoP 8.5.16) – https://stevemiddlehurst.wordpress.com/2014/08/10/w-eugene-smith-ww2-to-minamata/

(6) Smith, W.Eugene (1951) Village of Deleitosa in Western Spain. 1951 (accessed at Magnum 8.5.16) – http://www.magnumphotos.com/Catalogue/W-Eugene–Smith/1951/SPAIN-Village-of-Deleitosa-in-Western-Spain-1951-NN145579.html