John Szarkowski believed that Diane Arbus’ “enlarged sense of reality” made her work unique but he also saw that there was value in helping her contextulise her contemporary anthropologies and in 1964 encouraged her to study August Sander’s work (1). It is not clear to what degree Arbus was directly influenced by Sander, she refers more to Louis Faurer, Robert Frank and Lisette Model, but the similarities in terms of composition, directness and the desire to collect specimens are quite obvious. However, whilst Sander’s intent is not only clear but really very simple Arbus is one of the most enigmatic photographers of her generation. She was a complex, driven, intellectual, artistic and insecure women who felt her work was misunderstood in her own lifetime and who continues to divide opinion over forty years after her suicide in 1971, an act that in itself clouds the interpretation of photographs.

Her pictures are studied and analysed, dissected and interpreted but what would those same critics read into the few portraits of the artist herself ? Judith Thurman argues that “It seems fair to interrogate an artist in the same spirit” ( “Who are you?” and “How did you become what you are?”) — “particularly, perhaps, in the case of a photographer like Arbus, whose problematic intimacy with troubling subjects … and unseen yet palpable presence in the frame generate so much of the mystery that draws one to the images.”.(2)

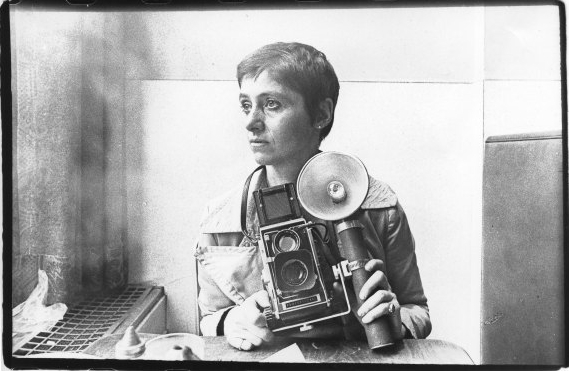

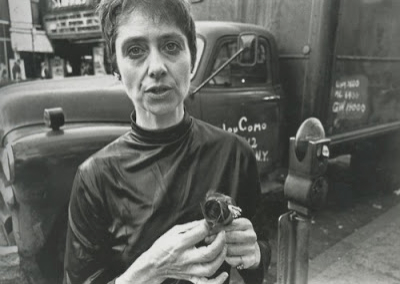

The photograph above was taken in 1968 by Roz Kelly (i) showing Arbus in the 42nd Street Automat on Sixth Avenue, New York (3). Kelly was a showbiz photographer who had met Arbus at the New Documents exhibition (ii) the year before; a meeting that led to Arbus photographing Kelly posing as Marilyn Monroe (1) so this photograph might have been the return fixture or just a chance meeting.

In Kelly’s portrait Arbus holds a Mamiya C33 with a press-style flashgun attached; she looks away from the photographer and out of the window. This lack of connection with the photographer contrasts with Arbus’ own work which is notable for the level of direct engagement and eye contact with her subjects; the lack of such engagement might signify her discomfort at being the subject or a lack of empathy with the young showbiz photographer (iii). Her large eyed stare beneath her impish haircut is the most striking feature, we know she had “luminous green eyes” (2), her neutral expression and slumped shoulders speaks less of confrontation and more of resignation but even in her mid-forties, ravaged by depression and the hepatitis she had contracted in 1966 she retains what Thurman calls her “nubile aura” but seems to hide behind the camera; it continues to separate and protect her from the world even when at rest.

Kelly interprets her pose as: “She looked as if she was on a cloud and about to take off. She took off alright, I never saw her again.” (1)

An alternative view is provided by Garry Winogrand who as just five years her junior was a direct contemporary and stalking the same New York streets in the sixties. Having both featured, along with Lee Friedlander, in John Szarkowski’s 1967 New Documents exhibition at the MoMA they are often discussed together despite their sharply contrasting styles. In his Central Park portrait of Arbus Winogrand captures her at work, a daffodil between her teeth, photographing a woman.

In a typical, energy filled Winogrand composition, Arbus calmly engages with her subject amidst the chaos of, what we are told, was a “love-in” (iv) but was billed as a “be-in” in its day. Winogrand’s picture highlights the difference between them, she is seeking out the individual faces whilst he is capturing the larger picture.

The Village Voice archives (5) suggest that this event became increasingly more bizarre as the sixties progressed so it is no surprise that Arbus was here looking for the marginals of New York society. Patricia Bosworth (1) says that she had come to photograph the event with Winogrand and a Village Voice photographer, Fred McDarrah.

Her eyes yet again capture one’s attention, strong, focussed, determined, a women engaged in her profession, business-like but with a faint hint of a smile in her expression, a softness, as she sizes up her subject, that was not present in Kelly’s formal portrait.

In McDarrah’s picture from the same day, she looks much younger, more the fey impish girl that many of her contemporaries describe. Once the camera is lowered she appears vulnerable, a transformation from the hardworking professional photographer to someone less certain, less assured.

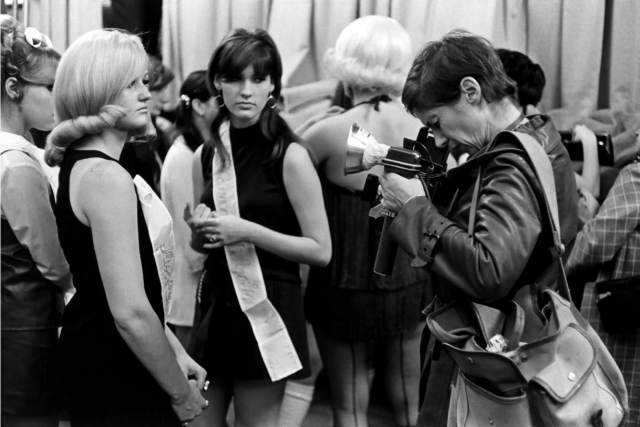

Two years previously William Gedney (7) had captured her at work photographing the contestants in a beauty pageant, a potentially misleading image that reads more as Arbus the press photographer for a small regional newspaper that Arbus the documentarist or portrait artist. Her subjects look suitably bored with the experience of being photographed.

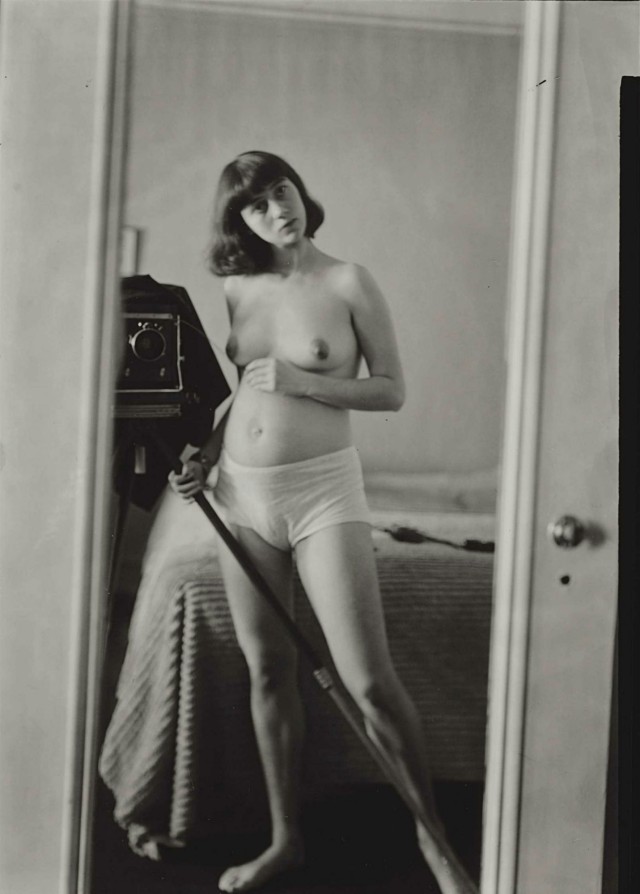

Arbus was married in 1941 at the age of eighteen to Allan Arbus (v) and was pregnant with their first child, Doon, when she took her self portrait. This is an intriguing photograph and probably less usual in 1945 than it was to become in the 21st century. A photograph taken to send to her husband who was serving in the armed forces in Burma; he had not known she was pregnant when he left so this photograph would have held great significance to both the photographer and the recipient. Her gaze and tilted head might be read as quizzical rather than coquettish, her nudity factual rather than sexual but her arm underlines her breasts more than it draws attention to her pregnancy and her gaze is firm enough to avoid any suggestion of vulnerability. We know from her sister, Renée that Arbus was aware of her own sexuality from a very early age (1) so it would be naive to think that this picture only records the early signs of her pregnancy and is not also sexually charged.

The inclusion of the camera suggests that photography is already part of her identity so this picture appears to reflect four important aspects of her character, the photographer, the sexual being, the mother-to-be and the independent young women in a single frame.

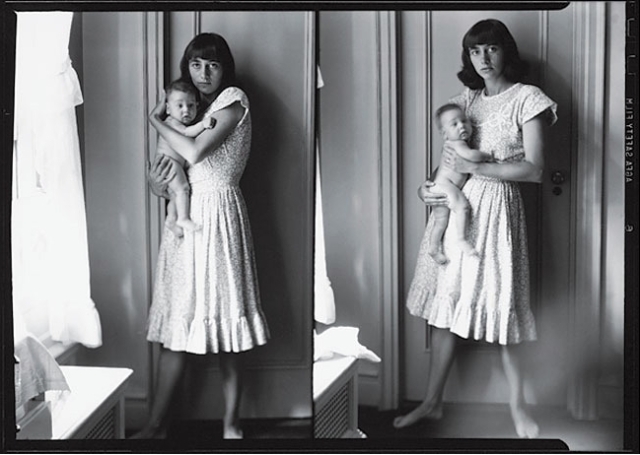

Later that same year, after Doon’s birth, she again turned to self portraiture to record her motherhood. One must assume that these pictures were also posted to Allan as he didn’t return from overseas until 1946. The poses potentially represent two identities, on the left she is nurturing and protective, the baby is firmly held close to her face, she envelopes the child and they both look towards the camera, her pose signifies motherhood, a strong statement that, in Allan’s absence, she is protecting their child.

To the right she has a strong, conviction-filled stare. The baby is held further from her face, less possessed and owned by the mother as she confronts the camera, her lips slightly parted, eyes wide open and locked in eye contact with the imaginary photographer or with Allan; the same independence and sexuality that was present in her pregnancy portrait.

Much later in 1963 Lee Friedlander (8) photographed her with Amy, her second child. This is the only image I have found of Arbus smiling, she looks away from the camera but the hand on her daughter’s head is possessive and loving. Amy’s arms are wrapped around her mother’s legs. They are content and relaxed in Friedlander’s company. Her face has the impish youthfulness that those who knew her speak of and this portrait of Arbus the contented mother declares her devotion to Amy. She wrote “My parenthood is such a joy, its the one thing that makes me feel big.” (1)

In 1970 Saul Leiter captured a series of portraits if Arbus (vi). She is posed in front of a wall of her own prints and what appear to be magazine cuttings. Bill Jay, amongst others, describes the walls of her bedroom as being “plastered with prints” that she was “living with” (4) as she decided whether they held any merit. This picture offers two insights; the photographer’s methods and her physical appearance at the age of 47. The photographs in question include some from her controversial series of “retardates” which represent the culmination of a career built on seeking subjects who did not or could not hide behind a mask but revealed their true inner self to her camera. In this picture she is gaunt, her illnesses had resulted in severe weight loss and her face, the bags under her eyes and exposed neck all suggest an older women. Her expression could be described as resigned but also hints at irritation or the discomfort in being the subject, much earlier she had said “I think it does, a little, hurt to be photographed.” (10)

Another portrait of Arbus was captured by Mary Ellen Mark in 1969. Apart from providing even more vivid evidence of Arbus’ weight loss in the year after being diagnosed with hepatitis this street portrait of her adds little to our knowledge. It is mainly of interest because it was taken by a Mary Ellen Mark a photographer who is often compared, sometimes unfavourably, with Arbus. Mark shared Arbus’ interest in psychological and intimate portraits. I am intrigued by the object in Arbus’ hand but have been unable to identify it.

These few portraits of Diane Arbus answer neither of Thurman’s questions “Who are you?” and “How did you become what you are?”; they show her external identities as a woman, a mother and as a photographer and suggest thoughtfulness, intellect and sexuality and to some degree chart her physical changes over a thirty-five year period (vii) but fail to reveal anything of her complex relationships with her parents, siblings, husband, lovers and photographic subjects, the motivations behind the huge energy that she invested in her short career or the reasons for her untimely and tragic death. Perhaps this just proves her own idea that “a photograph is a secret about a secret, the more it tells you the less you know” (9).

Arbus herself could spend days trying to capture a single frame that revealed something of the inner person so she is unlikely to have expected that these snapshots would answer any of the questions that still revolve around her life. She once told Joseph Mitchell that “she wished she could have photographed the suicides on the faces of Marilyn Monroe and Hemmingway ‘It was there. Suicide was there.'” but is it not here in these portraits of the artist.

Richard Avedon said “Nothing about her life, her photographs or her death was accidental or ordinary.”

Notes on Text

(i) Roz Kelly is herself an interesting character. In the late 60’s she was a staff photographer for New York Magazine where she photographed Jimi Hendrix, Leonard Cohen, Cream, Andy Warhol, Neil Diamond and Diane Arbus (3). She went on to have a rather patchy career in TV light drama including roles in Happy Days and Starsky and Hutch.

(ii) New Documents was curated by John Szarkowski and held at The Museum of Modern Art from February 28th to May 7th of 1967. (8)

(iii) Based on Bill Jay’s (4) account of his meeting with Arbus that same year and Garry Winogrand’s comment that “she hated having her picture taken” (1) it is clear that she was not readily accessible to the press which might go some way to explaining why so few portraits of her appear to exist. I found one nude photograph of Diane by Allan but as her face was excluded it offered little to this exercise. There are also a small number of portraits of Allan and Diane as a couple but they are very formal shots that were possibly taken in the early days of the Diane and Allan Arbus Studio

(iv) The daffodil in Arbus’ mouth suggests that this event was the Easter Sunday “Be-In” which had become a regular event in the mid to late sixties. The 1967 event according to the archives of the The Village Voice (5) began as a medieval pageant when 10,000 hippies laden with daffodils gathered on a hill overlooking Central Park’s Sheep Meadow. “Bonfires burned on the hills, their smoke mixing with bright balloons among the barren trees and high, high above kites wafted in the air. Rhythms and music and mantras from all corners of the meadow echoed in exquisite harmony, and thousands of lovers vibrated into the night. It was miraculous.” but by 1969 it appears to have been losing some of its originality the Village Voice reported that the 1969 Easter Be-In/was a dismal event. “Every year it gets a little larger, slightly more exaggerated, a bit further out, a mite more bizarre, and altogether hairier than the year before.” (6)

(v) Another interesting character; Allan Arbus had studied photography in the New Jersey Signal Corps and worked with Diane as a Fashion photographer in the 40s and 50’s. After they separated in 1959 she continued to develop his films until in 1969 he moved to California to become and actor. He is best known as Dr. Sidney Freedman the unit psychiatrist in M.A.S.H..

(vi) I have only tracked down this one but Schultz (10) describes them as a series.

(vii) Something few of us would find flattering.

Sources

Books

(1) Bosworth, Patricia (1984) Diane Arbus: A Biography. London: Vintage Books

(4) Jay, Bill (1992) Occam’s Razor. Tucson: Nazraeli Press

(8) Friedlander, Lee (2015 ) Children: The Human Clay. New Haven: Yale University Press

(9) Arbus, Diane. (1972) Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph. Fortieth anniversary edition 2011-2012. New York: Aperture.

(10) Schultz, William Todd (2011) An Emergency in Slow Motion: the Inner Life of Diane Arbus. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Internet

(2) Thurman, Judith (2003) Exposure Time: Diane Arbus’ Estate Opens up her Life and Work to New Scrutiny. (accessed at The New Yorker 1.1.16) – http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2003/10/13/exposure-time

(3) Kelly, Roz (accessed at Getty Images 30.12.15) – http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/galleries/photographers/roz_kelly

(5) McNeill, Don (1967) Central Park Rite is Medieval Pageant (accessed at The Village Voice 1.1.16) – http://www.villagevoice.com/news/the-1967-central-park-be-in-a-medieval-pageant-6662021

(6) Migliore, Elizabeth (2004) Peace, Love and Central Park (accessed at His373 1.1.16) – http://his373.tripod.com

(7) Gedney, William. Diane Arbus Photographing at Beauty Pageant (accessed at Duke University Libraries 1.1.16) – http://library.duke.edu/digitalcollections/gedney_NY0015/

(8) Szarkowski, John (1967) New Documents Press Release (accessed at MoMA 2.1.16) – http://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/press_archives/3860/releases/MOMA_1967_Jan-June_0034_21.pdf?2010